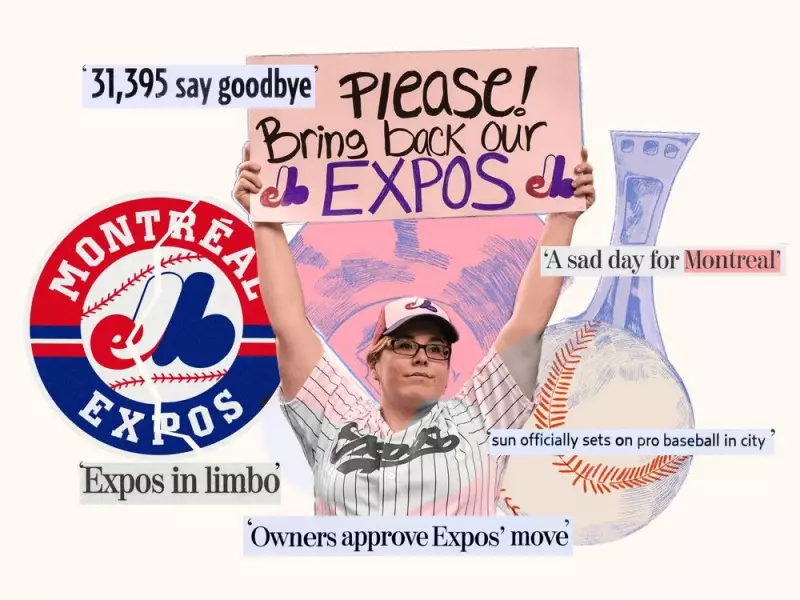

The question of who killed the Montreal Expos has resurfaced with a new Netflix documentary, reigniting a painful debate for baseball fans across Canada. As the Toronto Blue Jays' recent World Series loss to the Los Angeles Dodgers sparked nostalgia, The Gazette spoke with three central figures from the Expos' final years to uncover what truly went wrong behind the scenes.

The Beginning of the End: The 1994 Strike and Fire Sale

Montreal businessman Mark Routtenberg, part of the ownership consortium that controlled the Expos before their 2004 demise, points directly to the 1994-95 Major League Baseball strike as the catalyst for destruction. The Expos possessed baseball's best record at 74-40 when the strike began on August 12, 1994, with many believing they were destined for World Series glory that never materialized.

When the strike finally ended on April 2, 1995, managing partner Claude Brochu orchestrated what became known as the "fire sale," trading star players like Marquis Grissom, Ken Hill, and John Wetteland while losing Larry Walker to free agency. The team finished last in their division that season and never recovered.

"That was the beginning of the ruination of the club," Routtenberg stated, noting it also ended his friendship with Brochu. He placed significant blame on his fellow consortium members from Quebec's business elite, including the Desjardins Group, Jean Coutu Group, Bell Canada, and even the City of Montreal.

"My partners were stupid," Routtenberg said bluntly. "They were heads of corporations who knew f— all about baseball and sports. Quebec Inc. zero. They didn't even want to come to games at the beginning."

The Loria Era: A Controversial Turn

Both Routtenberg and David Samson, who ran the Expos when New York art dealer Jeffrey Loria purchased a 24% stake for $18 million in 1999, acknowledged Loria's understanding of sports franchise economics. "Loria had it right from Day 1," Routtenberg explained. "He's an art dealer. So he understands supply and demand. He said: 'There's only 32 of them in the world. It has to go up in value.'"

When Loria issued mandatory cash calls that local owners refused to meet, his ownership percentage ballooned to 94%. Ultimately, Major League Baseball purchased the Expos for US$120 million in 2002, providing Loria most of the funds needed to buy the Florida Marlins for US$158.5 million. After two years under league management, the Expos relocated to Washington in 2004, becoming the Nationals.

Samson defended their actions, stating that MLB commissioner Bud Selig wanted local ownership but found no takers. "Every local businessman had an opportunity to invest in that team," Samson noted, emphasizing that Loria's initial investment was relatively modest at $18 million Canadian.

Samson claimed governmental support for a new stadium never materialized despite early assurances. "The team couldn't stay at Olympic Stadium; the MLB would not allow it," he said, placing responsibility squarely on the Quebec business leaders who he believes "set us up" to take the fall.

Missed Opportunities and Lasting Regrets

Stephen Bronfman, whose father Charles originally owned the Expos from 1968 to 1991, had a small stake during the Loria era and recently led efforts to bring MLB back to Montreal. He echoed Routtenberg's criticism of the local ownership group's understanding of sports business.

"Back then, there was a chance, but nobody would step up," Bronfman lamented, comparing the situation to when Molson Breweries sold the Montreal Canadiens to American George Gillett Jr. in 2001 without Canadian buyers emerging.

Bronfman described frosty relations with Loria from the beginning, recalling how during spring training in West Palm Beach, Loria seated French-Canadian partners separately from his own group. "It was very uncool... It doesn't take a rocket scientist to figure out there might be an ulterior motive," Bronfman noted.

Despite recent efforts to bring baseball back through a shared team arrangement with Tampa Bay, Bronfman acknowledged that "Major League Baseball shot down" the proposal. He remains convinced that had the 1994 team been kept together, Montreal would still have baseball today, quoting Larry Walker's belief that team could have won "one or two, at least, World Series."

All three men ultimately pointed to collective failure. Routtenberg summarized it as "collective blame," including himself for both bringing in Loria and failing to prevent the fire sale. Bronfman concluded simply: "Everybody was to blame, myself included."