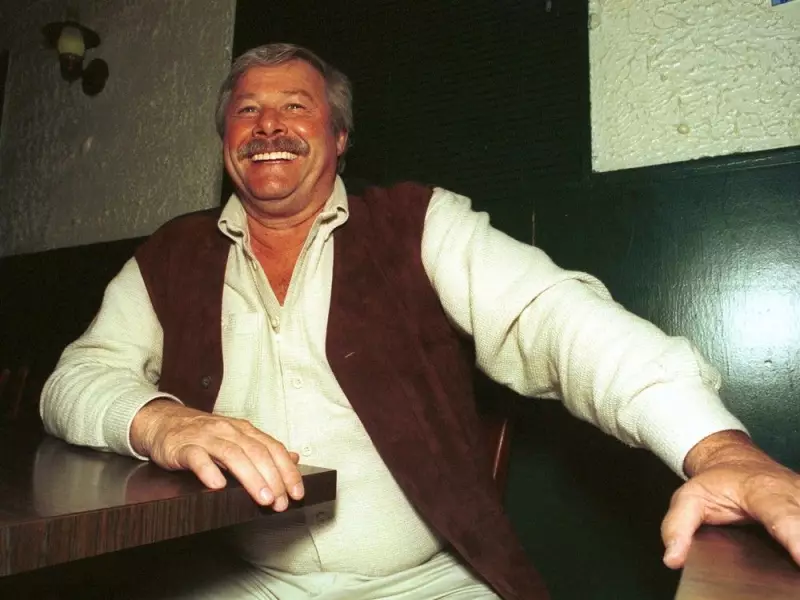

Gerald Matticks, the alleged leader of Montreal's West End Gang who was often called the city's 'king of coke,' has died at age 85. His family announced his passing on Facebook on November 22, 2025, stating he died of natural causes.

The Rise of a Montreal Crime Figure

According to crime journalist Julian Sher, Matticks represented the Irish and anglophone community in Montreal's underworld, much like Vito Rizzuto represented the Italians and Maurice Boucher represented the Hells Angels. Born on July 4, 1940, as the youngest of 14 children, Matticks grew up in Goose Village, a working-class Irish Catholic neighborhood near the Victoria Bridge.

Matticks quit school at age 12 after slapping a teacher who was disciplining him and jumping out a window. He married at 17 and had four children by age 21. Throughout his life, he claimed to have dyslexia and never learned to read properly, relying on others to handle written documents.

Through the 1970s, Matticks and his brothers were repeatedly linked to truck hijackings and stolen goods. A major public inquiry into organized crime in the late 1970s featured the Matticks clan as faces of what became known as the West End Gang. Though acquitted, the nickname stuck.

Controlling Montreal's Port and Drug Trade

In 1984, Matticks became president of the Coopers and Checkers Union at the Port of Montreal, representing workers who handled and verified containers. Investigators later claimed this position effectively made him gatekeeper to what went in and out of the port.

During a port strike, only one truck reportedly rolled out - Matticks' truck, which was allegedly filled with drugs according to Julian Sher, who directed the documentary The Kings of Coke about him. This control meant other major crime figures, including the Hells Angels, needed to negotiate with him. The bikers referred to him as 'the boeuf.'

In May 1994, the Sûreté du Québec arrested Gerald Matticks and his brother Richard in Operation Thor, accusing them of importing more than 26 tonnes of hashish through the port. The case collapsed when it emerged investigators had altered shipping documents as evidence, leading to the Poitras Commission inquiry that concluded provincial police had broken the law.

Conviction and Complex Legacy

Despite the failed hashish case, evidence from biker trials suggested Matticks reached his peak influence between 1994 and 2001, becoming the main supplier of hashish and a key facilitator of cocaine shipments for the Hells Angels' Nomads chapter.

In March 2001, Matticks was arrested with over 120 bikers and associates in Operation Printemps 2001, the largest anti-gang sweep in Quebec history. The following year, he pleaded guilty to being a major supplier to the Hells Angels in exchange for not being extradited to the United States.

Prosecutors said 33,000 kilograms of hashish and 260 kilograms of cocaine had passed through the port with his help. He received a 12-year sentence. At a 2009 parole hearing, he admitted: 'I was the big guy in there. Without me, it wouldn't have happened. I was the key man.'

Throughout his criminal career, stories persisted about his generosity. Many remembered him giving out Christmas turkeys, envelopes of cash, donations for church repairs, and quietly helping neighbors who struggled to buy groceries. His son described him as someone who loved Christmas and driving around with Santa handing out toys and food.

After serving his sentence, Matticks retreated to his farm. Unlike many organized crime figures, he didn't die in prison or by violence. As Julian Sher noted, 'They had no international ambitions. They were local boys who were content to be kings of coke in Montreal.'