From Gaza to Israel: A Convert's Warning About Islamist Extremism

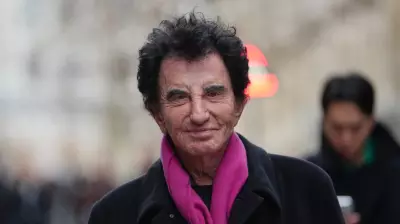

Dor Shachar, who was born Ayman Abu Soobuch in Khan Younis, Gaza, in 1977, now lives as a Jewish convert in Tel Aviv. With his distinctive black ponytail and confident presence, he embodies an Israeli identity that starkly contrasts with his upbringing in a culture steeped in anti-Jewish sentiment.

A Childhood Shaped by Contradictions and Violence

Shachar's earliest lessons about Jews came from his own grandfather, who would paradoxically invite Jewish visitors for coffee and bread while simultaneously urging his grandson to "free the land" by killing Jews. "I said to myself, 'how can it be? On one side he invites them for food and drink, and on the other he says to kill them.' From a young age I understood something is wrong," Shachar recalled.

Growing up in the alleys and markets of Gaza, Shachar witnessed the rise of Hamas and other terror factions long before the group's electoral victory in January 2006. He emphasizes that Hamas's ideology represented not just the armed militants but the broader culture that elected them. "Who chose Hamas? The majority chose Hamas," he told the National Post.

Firsthand Encounters with Future Terror Leaders

Shachar's childhood neighbors included individuals who would later become notorious figures in Palestinian militant groups. He knew Yahya Sinwar, Mohammed Deif, and bombmaker Yahya Ayyash well, describing them as "community faces" alongside others from Hamas, Islamic Jihad, Fatah, and the PLO. He was aware that some neighbors, including his own brothers, had killed Israelis.

The violence was not abstract or distant. Shachar recalls witnessing Sinwar sever the head of a Palestinian accused of collaborating with Israel in the open market, surrounded by cheering onlookers. On another occasion, he and his mother discovered a head in the market street, with bystanders showing little reaction beyond noting the victim was "suspected of cooperating with Israel."

Systematic Indoctrination from Childhood

The anti-Jewish messaging permeated every aspect of Gazan society during Shachar's youth. Children's television shows explicitly preached "'go and kill the Jews.'" In mosques, sheikhs proclaimed that killing Jews was "the greatest commandment" and "Allah's will."

Even schools run by the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA) propagated similar hatred. Jewish people were described as "pigs, dogs and infidels" who did not deserve to live. Children were told Israelis had one eye in their forehead or three legs, creating dehumanizing caricatures of the Jewish people.

"But I knew the soldiers, and they'd given me candy sometimes. They don't have one eye in the forehead—they aren't like that," Shachar noted, recalling his personal experiences that contradicted the propaganda. "The Jews who came to the market in Khan Yunis to give us food aid didn't have one eye in the forehead. The Jews who came to the weddings of our neighbours didn't have three legs or an eye in the forehead."

Education as a Tool for Violence

Violence was systematically incorporated into the educational curriculum. "Every child learned how to throw stones at Jews because they teach it," Shachar explained. "The teacher would tell us to go out and throw stones; then come back and open books as though we were studying. When the soldiers came, they saw little children studying. After the soldiers left, the teachers laughed—'these pigs, these dogs, these betrayers, these Jews, we will slaughter them like Hitler did.'"

A Personal Transformation and Warning

Shachar's journey from Ayman Abu Soobuch to Dor Shachar represents a profound personal transformation. "I wanted to be a Jew because I chose life, I chose love and not hatred," he explained about his conversion to Judaism.

Now living in Israel, Shachar offers a stark warning to Western nations about the dangers of Islamist ideology. Having watched Hamas's rise from within Gazan society, he believes the group reflects the culture that elected them and cautions that similar extremist ideologies could spread beyond the Middle East if not properly understood and addressed.

His firsthand account provides unique insight into how extremist ideologies take root in communities, how violence becomes normalized, and how propaganda shapes perceptions from childhood. As someone who has lived on both sides of this conflict, Shachar's perspective offers valuable context for understanding the complex dynamics at play in the region and beyond.