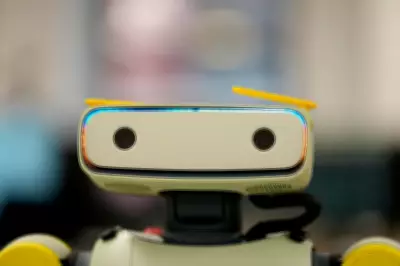

In a thought-provoking column, journalist Colby Cosh delves into the double-edged sword of the artificial intelligence revolution, arguing that while the future imagined in science fiction is now at our doorstep, it arrives laden with profound and potentially catastrophic risks. Cosh reflects on public intellectual Noah Smith's recent essay, which expressed a personal fondness for generative AI bots, the kind of multilingual, intelligent assistants that have been a staple of futuristic visions for a century.

The Public's Hostility and History's Warning

Cosh notes that despite Smith's delight, the broader public reaction to these AI "creatures" appearing overnight is dominated by hostility and suspicion. He draws a parallel to historical technological leaps, reminding readers that the benefits of progress are often only clear in retrospect. We may laugh at the Luddites who resisted mechanization, but they were individuals whose livelihoods were genuinely threatened, a cautionary tale for today's AI disruption.

The columnist emphasizes that the "bad initial effects" of new technology are not trivial. He provides a stark historical panorama: the printing press ignited religious wars, railways and the telegraph enabled the unprecedented carnage of the First World War, and 20th-century totalitarian ideologies flourished through the novel power of mass media. Cosh points to the ongoing conflict in Ukraine, where an AI-driven drone arms race is evolving at breakneck speed, as a chilling, real-time example of how this technology can destabilize global political order.

Surviving the One-Way Door of Progress

Despite these sobering historical precedents, Cosh acknowledges humanity's resilience. Our species has survived these epochal crises, escaping Malthusian traps to reach an era of relative plenty. The fundamental truth, he states, is that technological leaps are one-way doors; there is no going back, only moving forward through the challenges they present.

Turning to the consumer AI tools that are captivating and unnerving the public, Cosh offers a blunt and memorable prescription for engagement. He insists these systems, while marvelous, must be regarded for the moment as insane. Their trustworthiness, he argues, should extend only as far as one would trust a genuinely insane human being. A critical, unanswered question hangs over the field: to what degree can this fundamental instability be corrected?

Finding Use for a Hyper-Intelligent, Unstable Companion

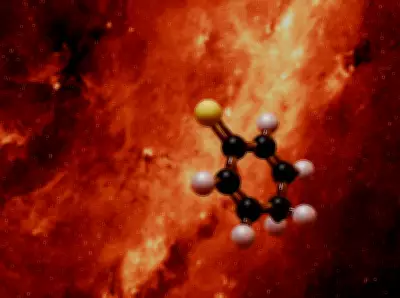

Echoing Noah Smith's pragmatic approach, Cosh admits to finding an ever-growing list of practical applications for these flawed digital minds. He dismantles the expectation of perfection, noting that fallibility is a human and fictional constant. From C-3PO and the Star Trek computer getting things wrong to the mistakes of every human, news site, and social media feed, infallible omniscience remains beyond engineering.

The core lesson, Cosh concludes, is one of rigorous verification. Just like any other source of information or assistance encountered in life, AI outputs must be cross-checked before being fully believed. The arrival of the AI future is undeniable, but navigating it safely demands a blend of awe, utility, and profound, well-informed caution.