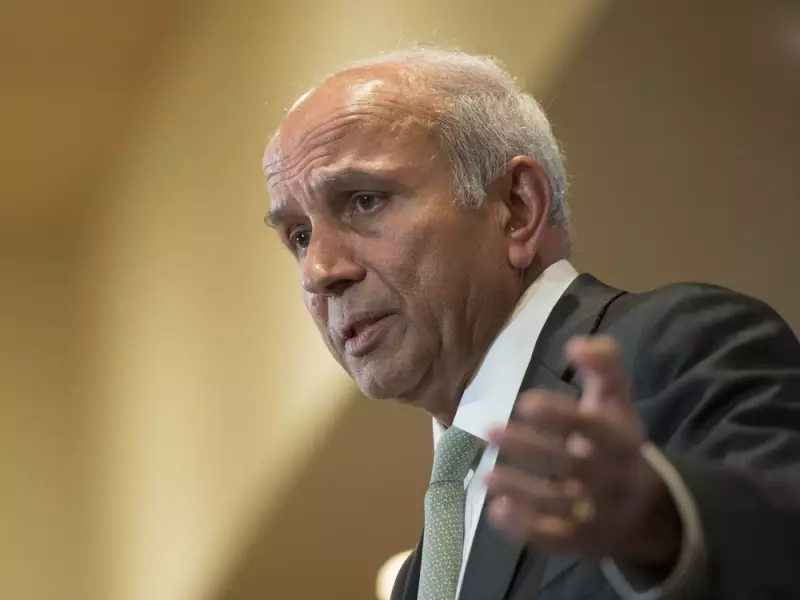

In the early months of 2007, while most financial institutions remained blissfully unaware of the gathering storm, Prem Watsa, chief executive of Fairfax Financial Holdings Ltd., gathered with his investment committee for their regular strategy session. The question Watsa posed was familiar to everyone in the room: "What's the best idea we've got?"

The Unpopular Bet That Cost Millions

Brian Bradstreet, Fairfax's bond specialist, kept silent during that fateful meeting. The company had already invested US$341 million in a contrarian position that was bleeding money, with paper losses reaching US$211 million by 2007. At any other financial firm, Bradstreet later acknowledged, he would have been "kicked out on the street" for championing such a losing trade.

Fairfax had established a pattern throughout its history of being early on major market shifts. The company had prematurely exited Japanese stocks during the 1980s bubble, missing the final manic surge to the peak. Similarly, they endured significant losses preparing for the 2000 technology wreck before ultimately profiting handsomely. Their current big trade followed this familiar pattern - an expensive contrarian call that had yet to pay dividends.

The Psychology of Waiting for Disaster

With the benefit of hindsight, shorting the financial crisis appears straightforward. The reality for those living through the wait was anything but simple. As quarters turned into years with mounting losses, the mental and financial toll tested even the most seasoned investors' resolve.

Fairfax wasn't alone in facing this challenge. Legendary investor Julian Robertson closed his Tiger Management hedge fund in March 2000, just as the technology bubble reached its peak. After two years of shorting runaway tech stocks, he exhausted both his patience and capital, quitting the marathon mere feet from the finish line. Laurence Tisch, CEO of Loews Corporation, similarly abandoned his short positions after four years and US$2.5 billion in losses, missing the market peak by months.

Doubling Down When It Hurt Most

Back in that 2007 meeting, as Bradstreet remained silent, it was soft-spoken colleague Francis Chou who broke the tension. His recommendation was counterintuitive: "Buy more credit default insurance."

"We swallowed hard and purchased some more," Watsa recalls. The decision to increase their bet against financial companies with exposure to mortgage securities came despite already substantial paper losses. The value of their position continued moving in the wrong direction into June 2007.

That summer, however, the predicted storm finally hit financial markets. The mortgage security bubble burst, and Fairfax found itself perfectly positioned to profit from the chaos. What began as a defensive measure to protect Fairfax's capital transformed into a financial windfall.

In his assessment to shareholders after the crisis, Watsa reflected soberly: "All of the investment risks that we worried about and have written to you about for at least the past five years simultaneously reared their ugly head, as the 1-in-50 or 1-in-100 year storm in the financial markets landed in the fall of 2008."

While Watsa noted that there were "very few places to hide, let alone prosper" during the financial collapse, his understatement concealed the truth: Fairfax had not only found shelter from the storm but had emerged with a US$4-billion windfall from their prescient bet against the financial system.