Chief Kelly LaRocca has issued a powerful counterpoint to recent commentary, asserting that Canada has a fundamental duty to address the historical dispossession of Indigenous peoples. Writing in the National Post on December 19, 2025, LaRocca challenges oversimplified narratives, urging Canadians to understand the persistent tensions around Indigenous rights as a consequence of systemic policies that require correction.

Moving Beyond the "Settler" Narrative

LaRocca directly addresses arguments made by commentators Tom Flanagan and Mark Milke, who suggested that because everyone is a settler, no special obligations exist toward First Nations. She reframes the term "settler" not as a marker of race or moral failing, but as a descriptive political term. Citing political theorist James Tully, she explains it describes those whose ancestors established political authority in Canada without the consent of existing Indigenous nations.

This historical relationship, she argues, created a foundation lacking in equality, fairness, or reciprocity. The chief emphasizes that recognizing this is not about assigning guilt but about understanding the factual origins of current inequities.

The Limits of Symbolism and the Need for Action

A significant portion of LaRocca's argument focuses on the purpose and limitations of symbolic gestures like land acknowledgements. She clarifies that these were never intended to shame descendants of settlers. Their original goal was to correct a long history of erasing Indigenous presence from public life and to serve as a first step toward an ethical relationship.

However, LaRocca is clear that acknowledgements alone are insufficient and can even feel abstract or reinforce "othering" for many Indigenous people. She calls for institutions to replace or supplement them with "action statements"—concrete, contextual commitments tied to an organization's expertise. Effective actions could include goals in:

- Health equity and procurement

- Co-governance protocols and land stewardship

- Improving access to education, housing, clean water, and economic opportunities

Dispossession Was a Systemic Process, Not a Single Event

LaRocca counters the idea that Canada was "stolen" in one act, arguing instead that it was built through a cumulative and systemic process of dispossession. She points to specific historical policies and treaties that facilitated this process.

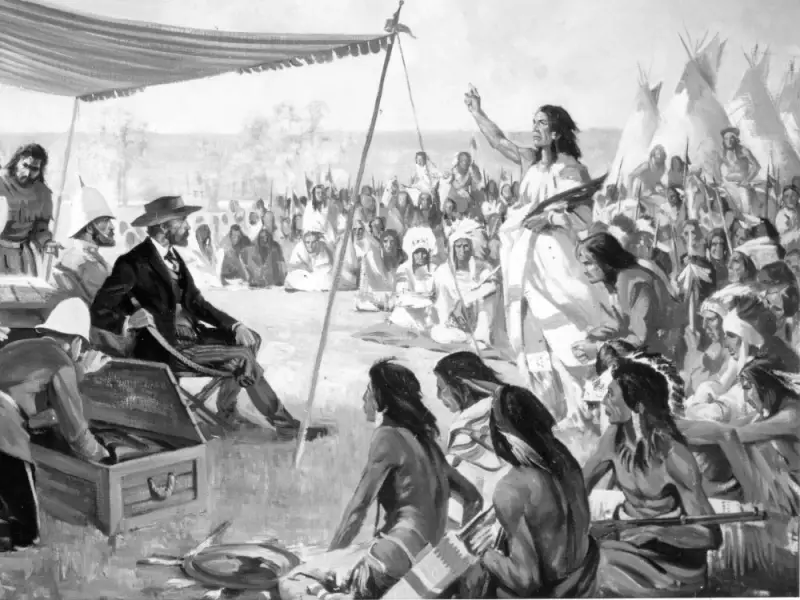

She highlights the Gradual Civilization Act (1857) and the Gradual Enfranchisement Act (1869), which imposed foreign governance models and eroded traditional Indigenous political systems. Furthermore, she notes that treaties like the Robinson Treaties and Numbered Treaties (including Treaty 7, signed with the Blackfeet Nation in 1877) were often negotiated during periods of Indigenous vulnerability and were later violated through unauthorized resource extraction.

LaRocca also addresses the concept of "time immemorial," which Flanagan and Milke misinterpret by linking it to human origins in Africa. She clarifies that the term refers to "as long as collective memory reaches" and is backed by archaeology and oral history showing Indigenous nations governed complex societies with diplomatic alliances and trade routes for millennia before European contact.

In conclusion, Chief Kelly LaRocca's argument is a call for a mature and responsible national conversation. She urges Canada to move beyond defensive simplifications and recognize the specific historical trajectory that created present-day inequalities. The path forward, she insists, lies in tangible, accountable actions that address the legacy of cumulative dispossession and build a truly reciprocal future.