As the son of two surgeons, Xavier Court is often asked if he plans to follow his parents into medicine. His answer is an immediate and resounding no. In a heartfelt opinion piece for the Montreal Gazette, the Marianopolis College social sciences student explains that a lifetime of watching his parents' sacrifices has shown him a healthcare system stretched to its breaking point—a system he believes Quebec's Bill 2 will not fix.

A Childhood Defined by Surgical Calls

Court describes a home life where family schedules were dictated by surgical call rotations. He learned about medical emergencies like ruptured spleens before mastering multiplication tables. Evenings often ended with the glow of his mother's laptop as she completed charts, answered patient emails, and prepared for rounds long after other parents were reading bedtime stories.

"The work never stops," he writes, painting a picture of physicians whose responsibilities bleed far beyond hospital walls. He recounts his mother dropping everything to help a colleague or a declining patient, even on her nights off, and hosting medical residents at their home on weekends. This relentless dedication led to a family joke: if he had a sibling, they would have been named Surgery.

Bill 2: A Demand for the Impossible

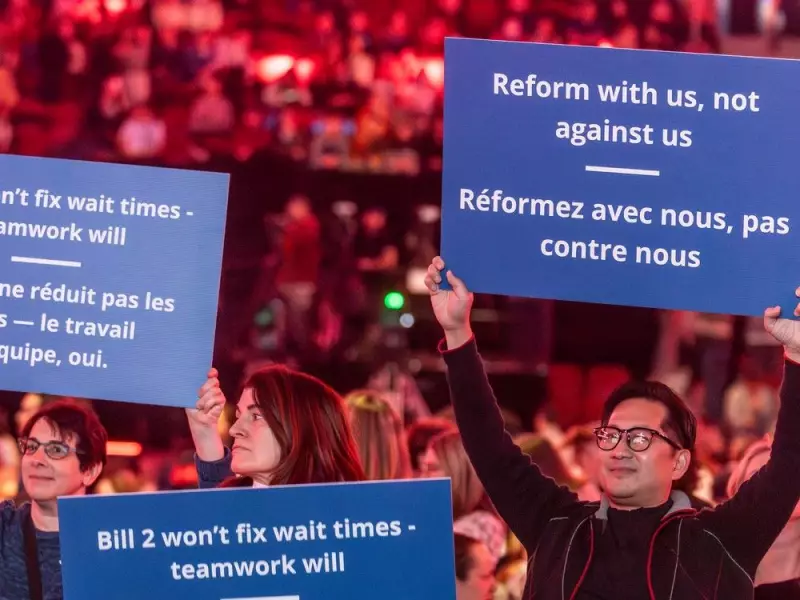

The Quebec government's adoption of Bill 2 in December 2025, which demands physicians increase patient output and "optimize" access without additional resources or structural support, filled Court with fear and heartbreak. He argues the law fails to address the core problems.

"I know there is simply no more time left to give," he states. He challenges political leaders to shadow a doctor for a full 24-hour cycle to understand the reality: surgeons finishing marathon shifts only to face hours of unpaid administrative work at home, all while managing an aging population with increasingly complex needs.

Heroes Now Portrayed as Obstacles

Court contrasts the pandemic-era celebration of healthcare workers as heroes with the current political narrative that often frames doctors as part of the access problem. He finds it galling that the same people who risked their lives are now being told the solution is simply to work harder and faster.

He insists his parents and their colleagues are not the issue. "They are Band-Aids holding a fractured system together," he writes, pointing to systemic shortages in operating room time, hospital beds, nursing staff, and clerical support. He emphasizes that delayed surgeries and long ER waits are symptoms of resource scarcity, not physician laziness.

His final plea is direct: if the government genuinely wants to improve healthcare access, it must start by asking physicians what they need and building solutions with them. Until that happens, his personal decision stands firm. He loves and admires his parents, but the life he has witnessed has convinced him: he will not become a doctor.