As the United States prepares to mark Bill of Rights Day on December 15, the foundational document's 234-year legacy offers a profound point of comparison with Canada's constitutional framework. Ratified in 1791, the first ten amendments to the U.S. Constitution were designed to explicitly limit federal power and protect individual liberties, a philosophical stance that remains distinct from Canada's approach to rights.

The Foundational Philosophy: Inalienable Rights vs. Government Grant

The core distinction lies in the underlying philosophy. The American system is built on the belief that rights are inherent and inalienable, possessed by individuals from birth. Government is seen as legitimate only when it refrains from violating these pre-existing rights. In contrast, Canada's Charter of Rights and Freedoms operates under a "reasonable limits" clause, allowing governments to curtail rights if such limits can be demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society.

This means that in the U.S. context, rights like free speech and religious exercise are viewed as negative liberties—restrictions on what government can do. The Canadian model often treats similar freedoms as positive rights that can be balanced against other societal interests.

James Madison's Reluctant Journey to Father of the Bill of Rights

The story of the Bill of Rights is deeply tied to James Madison, who initially opposed its creation. A key architect of the Constitution, Madison argued in the Federalist Papers that the new federal government's powers were "few and defined," with no authority to encroach on liberty. He feared that listing specific rights would imply that unlisted rights were not protected.

Madison believed in a broad, natural right to liberty, famously writing in 1792 that property was not just land, but that "a man has a property in his opinions and the free communication of them" and that "conscience is the most sacred of all property."

The Jeffersonian Persuasion and a Lasting Compromise

It was the persuasion of his mentor, Thomas Jefferson, that ultimately changed Madison's mind. Jefferson, aware of public skepticism toward the new Constitution, urged pragmatic action. In a pivotal argument, he wrote to Madison that the document should guard against governmental abuses of power, concluding that "half a loaf is better than no bread." If they could not secure every natural right in writing, they should secure what they could.

This pragmatic compromise led Madison to shepherd 12 proposed amendments through Congress. Ten were ratified by the states on December 15, 1791, becoming the Bill of Rights. An eleventh, concerning congressional pay, was remarkably ratified 201 years later in 1992.

An Enduring Legacy and a Transborder Dialogue

Today, the Bill of Rights stands as a living, though imperfect, check on government power. Its annual commemoration prompts reflection not just in the U.S., but also in neighbouring Canada, where debates about the scope and limits of rights continue within a different constitutional structure. The historical dialogue between Madison's ideal of unenumerated natural rights and Jefferson's pragmatic push for enumerated protections continues to inform modern legal and political discourse across North America.

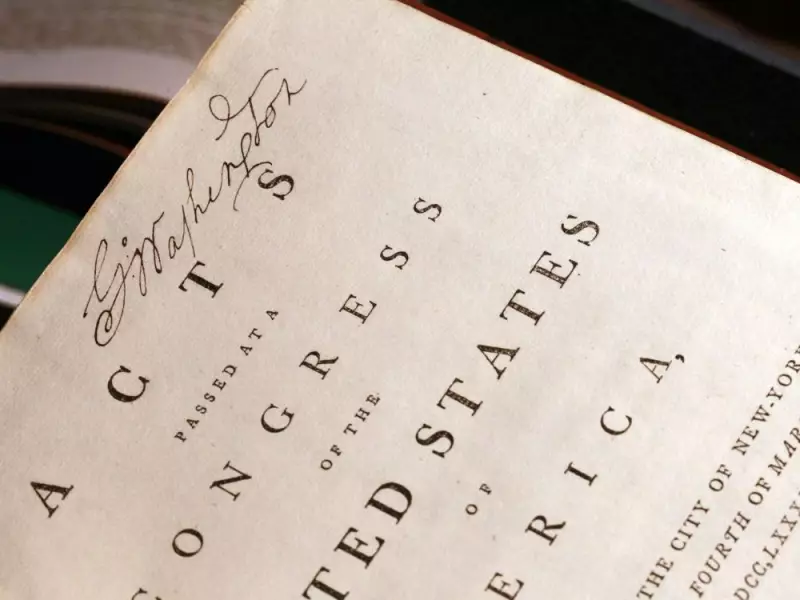

The physical symbol of this history—George Washington's personal copy of the Acts of the First Congress containing the Constitution and the proposed Bill of Rights—serves as a tangible link to the 18th-century debates that shaped a nation's fundamental relationship between citizen and state.